[wp_ad_camp_1]

Nubile Nubians [11th century BC – 4th century AD]

While looking up something entirely different, I came across this surprising reference to ferrets in a book called “Wonderful Ethiopians of the Ancient Cushite Empire”, written by Drusilla Dunjee Houston in 1926.

While looking up something entirely different, I came across this surprising reference to ferrets in a book called “Wonderful Ethiopians of the Ancient Cushite Empire”, written by Drusilla Dunjee Houston in 1926.

In Chapter IV entitled ‘The Amazing Civilization of Ethiopia’, she quotes a reference by Eliseé Reclus from his 1886 book “The Earth and its Inhabitants: Africa”.

Ancient Africans yoked the wild ox, tamed the cow, the horse and sheep. This is why animals play such an important part in the old Cushite mythology. Africans subdued the elephant as early as the Cushites of Asia. Ancient sculptures show the African lion tamed. These indefatigable men domesticated wheat, barley, oats, rye and rice, in fact all the staple plants of our civilization were fully developed so far back in the distant ages, that their wild species have disappeared. Think how helpless we would be today without them. Reclus declares, “We are indebted to the African for sorghum, dates, kaffir, coffee and the banana, also for the dog, cat, pig, ferret, ass and perhaps for the goat, sheep and ox. The first African explorers, found the country covered with cattle parks, in which the natives kept thousands and tens of thousands of cattle of remarkable breeds, rare skill being shown in their handling.

The Cushites are considered to be the earliest known Black African civilization which reached its peak around 1750-1500 BC and lasted till the 4th century AD. They ruled over all of Egypt from around 747-656 BC when King Piankhi conquered the rest of the country.

If this actually refers to Cushites, as in Nubians (present day Sudan), rather than Cushites as in Ethiopians (from Abyssinia), then that would confirm the suggestion that the ferret has been domesticated since the time of the Egyptian, wouldn’t it?. And it would therefore make my point below about the Pharaoh’s rat invalid.

Hmmmmm, interesting!

I will leave both opinions in so that you, dear reader, can make up your own mind about what to believe

Homer [c 9th or 8th century BC]

So many of us are familiar with Homer’s The Iliad.  In Book X, Homer has Dolon dressed in a skin of a grey wolf while having a cap of ferret skin on his head.

In Book X, Homer has Dolon dressed in a skin of a grey wolf while having a cap of ferret skin on his head.

Despite his sartorial elegance, old Dolon gets caught by Diomed, who promptly cuts his head off while he was still speaking.

Tsk tsk!

Ulysses takes the ferret skin cap off the talking head and offers it up, honouring Minerva.

Well, I guess that should teach us all not to wear our ferrets on our heads!

During Pharaoh’s day [c 2686 BC – 1070 BC]

There seem to be a number of people who maintain that ferrets were first kept in Egypt as rat catchers but I have been unable to verify this as fact.

There seem to be a number of people who maintain that ferrets were first kept in Egypt as rat catchers but I have been unable to verify this as fact.

Strabo talks about the ichneumon being an animal peculiar to Egypt in Augustus’ time.

This animal was a member of the Viverridae family (other animals of the same family being the mongoose, meerkat, genet, civet), and which used to attack snakes and eat crocodile eggs.

There was a legend about the ichneumon that said it crept into the mouths of crocodiles when they gaped and ate out their bowels!

This animal, also called “Pharaoh’s rat,” has a grey coat with black tail tufts and could easily have been mistaken for a ferret or weasel on ancient drawings or statues.

Both the ichneumon and the shrewmouse were associated with the sun god and were honored, particularly during the late Greco-Roman periods, with burial and a small bronze statuary.

A Biblical reference [c 450 BC]

Those of you who’ve read the King James Version of the Bible will be aware that in Leviticus, chapter 11, verses 29 and 30, there are the following references to both the ferret and the weasel :

Those of you who’ve read the King James Version of the Bible will be aware that in Leviticus, chapter 11, verses 29 and 30, there are the following references to both the ferret and the weasel :

11:29 These also shall be unclean unto you among the creeping things that creep upon the earth; the weasel, and the mouse, and the tortoise after his kind,

11:30 And the ferret, and the chameleon, and the lizard, and the snail, and the mole.

Leviticus is the 3rd book of the Pentateuch, or Torah, and is a collection of laws regulating activities such as sacrificial offerings, installation of priests, cultic purity (including dietary laws) and so forth.

Since it has been dated to around 450 BC, I guess that is pretty good proof that the weasel, at least, was known to the ancient Israelites all those many years ago. Was the ferret also known to them, I wonder, or was that just ye olde English translation?

Mmm, must check! I’ll let you know if I can find anything definite.

As other versions of the Bible use other animals such as the rat, the mole, the gecko and the shrew instead of our two magnificent mustelids, it’d be great to find out what the original texts had listed in those verses.

Well, I’ve scoured the Internet and the only thing I could find was a list of 613 commandments in the Torah, showing what is required, permitted and forbidden by God.

In the Parshah VaYikra (literal translation: ‘section Leviticus’) 11:29 there was the commandment — “The ritual uncleanness of eight low crawling creatures”.

That’s it! No description of those 8 low crawling creatures. I wonder why the King James Version chose the ferret and weasel as 2 of the 8 low crawling creatures.

And I mean, hey, since when do weasels or ferrets CRAWL, hmmm? Bounce, pronk, scamper, trot, yes – but crawl? I don’t think so!

Well, there’s an interesting article about the choice of the word “ferret” in the The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia for those of you who are interested to learn more.

Strabo [c 64/63BC – c 23AD]

Strabo was born in Amaseia (now Amasya, Turkey), the son of wealthy parents.

Strabo was born in Amaseia (now Amasya, Turkey), the son of wealthy parents.

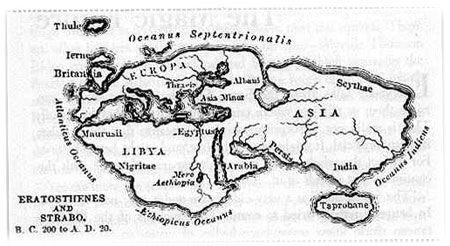

His “Geographia” is said to have been composed between 9-5 BC with parts revised around 18-19 AD.

Geographia

Book III, Chapter 2

There are exported from Turdetania large quantities of grain and wine, and also olive oil, not only in large quantities, but also of best quality. And further, wax, honey, and pitch are exported from there, and large quantities of kermes, and ruddle which is not inferior to the Sinopian earth. And they build up their ships there out of native timber; and they have salt quarries in their country, and not a few streams of salt water; and not unimportant, either, is the fish-salting industry that is carried on, not only from this county, but also from the rest of the seaboard outside the Pillars; and the product is not inferior to that of the Pontus. Formerly much cloth came from Turdetania, but now, wool, rather of the raven-black sort. And it is surpassingly beautiful; at all events, the rams are bought for breeding purposes at a talent apiece. Surpassing, too, are the delicate fabrics which are woven by the people of Salacia. Turdetania also has a great abundance of cattle of all kinds, and of game. But there are scarcely any destructive animals, except the burrowing hares, by some called “peelers”; for they damage both plants and seeds by eating the roots. This pest occurs throughout almost the whole of Iberia, and extends even as far as Massilia, and infests the islands as well. The inhabitants of the Gymnesian Islands, it is said, once sent an embassy to Rome to ask for a new place of abode, for they were being driven out by these animals, because they could not hold out against them on account of their great numbers. Now perhaps such a remedy is needed against so great a warfare (which is not always the case, but only when there is some destructive plague like that of snakes or field-mice), but, against the moderate pest, several methods of hunting have been discovered; more than that, they make a point of breeding Libyan ferrets, which they muzzle and send into the holes. The ferrets with their claws drag outside all the rabbits they catch, or else force them to flee into the open, where men, stationed at the hole, catch them as they are driven out. The abundance of the exports of Turdetania is indicated by the size and the number of the ships; for merchantmen of the greatest size sail from this country to Dicaearchia, and to Ostia, the seaport of Rome; and their number very nearly rivals that of the Libyan ships.

Isidore of Seville [c 560 – 636 AD]

Born in Cartagena, Spain, Isidore was known as a writer of a great many books, as well as being bishop of Seville.

One of the most well known books of his was “Etymologiae”, or “Origines“, as it is sometimes called, an ‘encyclopedia of all knowledge’. This book was considered extrmely valuable to the people who compiled bestiaries in later years and the information was used extensively.

Book XII, “Of beasts and birds”, is based on the writings of Pliny and Solinus and the viewpoint of scholars is that when he talks about the weasel which wanders about in houses, he is referring to the ferret.

Even though he doesn’t actually name the weasel a ferret, I can’t imagine another mustelid which fits that description so am quite happy to say that he was, in fact, talking about our favorite pet.

For you Latin speakers out there, here’s the original text of his work …

[3] Mustela dicta, quasi mus longus; nam telum a longitudine dictum. Haec ingenio subdola in domibus, ubi nutrit catulos suos, transfert mutatque sedem. Serpentes etiam et mures persequitur. Duo autem sunt genera mustelarum; alterum enim silvestre est distans magnitudine, quod Graeci IKTIDAS vocant; alterum in domibus oberrans. Falso autem opinantur qui dicunt mustelam ore concipere, aure effundere partum.

And for the rest of us whose Latin is rusty after all these years (ahem!!) …

3. Mustella (weasel) is so called, being, as it were, mus longus (long mouse); for telum (missile) is so called from its length. This creature, somewhat wily in its disposition, moves and changes its nest in the house when it is nursing its young. It chases snakes and mice. And there are two sorts of weasels. For one is a creature of the woods, and is of a different size, which the Greeks call iktidas. The other wanders about in houses. Now they have an erroneous idea who say that the weasel conceives in its mouth, and gives birth through its ear.

Translation by Ernest Brehaut, PhD, Studies in History, Economics & Public Law, Columbia University. 1912.

What I don’t understand is if Isidore says that the information about the weasel conceiving through its mouth is wrong, and his work was so valuable to compilers of bestiaries, why was the silly misconception about the weasel repeated erroneously in so many bestiaries?

Persian Gifts to China [638 AD]

I recently bought a book called “The Ambassadors: From Ancient Greece to Renaissance Europe, the Men Who Introduced the World to Itself” where, amongst other things, the author, Dr Jonathan Wright, PhD, discusses issues such as diplomatic immunity, diplomatic precedence and diplomatic gift-giving.

I was amazed to see listed the following diplomatic gift given by the Persians to the Chinese …

In 638 A.D. the Persians were sending the Chinese a ferret, that was an expert mice-catcher; a century later, they sent the Chinese four leopards.

Could this ferret have been the great-great-great-granddaddy of Genghis Khan’s ferrets, per chance?

[wp_ad_camp_3]

Deprecated: str_contains(): Passing null to parameter #1 ($haystack) of type string is deprecated in /home4/kitchast/public_html/wp-includes/comment-template.php on line 2684