[wp_ad_camp_1]

aka … polecat, foumart, foul marten, foulmart, fitch or fitchet.

For all you wordsmiths out there who want to know more about the origins of foulmart, check out Duncan Brown’s article, “The Foulmart: what’s in a name“, which was published in the Mammal Review in 2002. Read the pdf file here.

Etymology

polecat – 1320, first element is probably Anglo-Fr. pol, from O.Fr. poule “fowl, hen,” so called because it preys on poultry. The other alternative is that the first element is from O.Fr. pulent “stinking,” for obvious reasons. Originally the European Putorius foetidus; also applied to related U.S. skunks since 1688.

Online Etymology Dictionary, © 2001 Douglas Harper

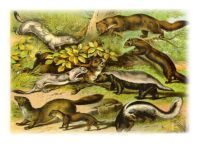

The European Polecat is the ferret’s kissing cousin and there’s been much discussion as to whether the ferret as we know it today (i.e. the sable ones) originated from it or another type of polecat.

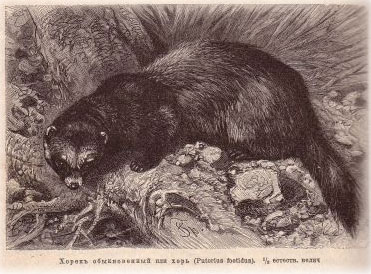

Appearance

Like the sable ferret, the European polecat has brown to dark brown guard hairs and buff/creamy-colored underfur. It has a white/creamy/yellowish patch on its face, around its nose and mouth. Some polecats have the light colored fur above their eyes as well, giving them a more distinctive “mask” look, and the tip of the nose is usually a dark brown color. I’ve read that polecats mark their territory by releasing a fetid secretion from the gland under their tails and, like ferrets, they “poof their stink bombs” when frightened.

Like the sable ferret, the European polecat has brown to dark brown guard hairs and buff/creamy-colored underfur. It has a white/creamy/yellowish patch on its face, around its nose and mouth. Some polecats have the light colored fur above their eyes as well, giving them a more distinctive “mask” look, and the tip of the nose is usually a dark brown color. I’ve read that polecats mark their territory by releasing a fetid secretion from the gland under their tails and, like ferrets, they “poof their stink bombs” when frightened.

I wonder if it’s just the males which do the scenting, like unsterilized male ferrets like to do. I can’t say that unsterilized girl ferrets do that sort of thing so am curious to know if the girl polecats do it or not. It sounds like a boy thing to me, I must say. Anyway, that’s why they got tagged with the Latin name Putorius foetidus, for obvious reasons

As you can see from this photo of our sable boy, CJ, when he was young, he could have passed for a European Polecat. I suspect that if we lived in England, he might even have been called a ferret-polecat hybrid but since we don’t have European Polecats in Australia, CJ most definitely was just a very stunningly dark ferret.

Their faces resemble minks rather than weasels with their skulls being slightly “boxy” and more canine in appearance than other weasels. They are solitary and primarily nocturnal animals but females with kits have been known to go out foraging during the day.

Their faces resemble minks rather than weasels with their skulls being slightly “boxy” and more canine in appearance than other weasels. They are solitary and primarily nocturnal animals but females with kits have been known to go out foraging during the day.

Size

Head and body length: male: 35-60cm; female: 30-45cm Weight: between 0.7 kg for females to 1.7 kg for males

Breeding[wp_ad_camp_2]

In England, mating takes place between March and April. The gestation period is 40-43 days, and there are usually 4-10 kits per litter.

Diet

Being a carnivore, the polecat eats rabbits, voles, small birds and rats but also includes snails, slugs, frogs and eggs in its diet. There are some websites which claim that the polecat is a strong swimmer and enjoys eating fish as well.

Lifespan

Polecats apparently have a lifespan of around 5 years.

Distribution & Habitat

Polecats range across Europe but studies in various countries like Luxembourg, Germany and Croatia seem to suggest that their population is decreasing, rather than increasing. Polecats were common throughout much of Britain in 1800 but by 1915 they were only found in mid Wales. However they are now found in most of Wales and are also reappearing in some parts of Scotland and places like Cheshire and Derbyshire in England, where there are Polecat Projects in place to monitor their movements and to see if their numbers are on the increase.

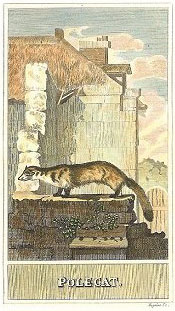

The European Polecat is mainly found in woodlands, farmlands and wetlands and often makes its den in stream banks or under tree roots.

Conservation Status

The European Polecat is considered Lower Risk Least Concern on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species website.

[wp_ad_camp_3]

Polecats in Ancient Times Aristotle mentions the polecat in his “Historia Animalium” written way back in 350BC … “The polecat or marten is about as large as the smaller breed of Maltese dogs. In the thickness of its fur, in its look, in the white of its belly, and in its love of mischief, it resembles the weasel; it is easily tamed; from its liking for honey it is a plague to bee-hives; it preys on birds like the cat.” Interesting to think that the polecat was mentioned back then and I wonder if it was the same animal as the European Polecat or another breed.

The Middle Ages in England

The first mention of polecats in medieval literature which I could find dates back to 1189, when Richard the Lionheart came to the throne after the death of Henry II.

That same year Colchester, a town in Essex, received the first known royal charter from King Richard, which gave the borough the foundations of self-government. Among other things was the right to hunt fox, hare or polecat within the liberty (borough bounds).

That same year Colchester, a town in Essex, received the first known royal charter from King Richard, which gave the borough the foundations of self-government. Among other things was the right to hunt fox, hare or polecat within the liberty (borough bounds).

Persecution by gamekeepers is the main reason that this species became temporarily extinct in England, mainly because of an archaic Tudor law called “The Preservation of Grain Act”.

Henry VIII passed it in 1532 by Henry VIII and Elizabeth I strengthened the Act in 1566, making it compulsory for every man, woman and child to kill as many creatures as possible that appeared on an official list of ‘vermin’. The list included otters, weasels, stoats, polecats, as well as hedgehogs!

There is more about the damage done to the English wildlife back in Henry’s day in a depressing book called “Silent Fields: The Long Decline of a Nation’s Wildlife“.

You can read the review of the book written in the Guardian newspaper.

You can read the review of the book written in the Guardian newspaper.

Here’s just one paragraph from the review describing the carnage wrought on these animals …

“Worse, at the same time railways were opening up even our wildest places. Barely had the Highlands been cleared to make way for sheep than huge tracts were turned over to grouse moor and deer forest. Intense persecution inevitably followed, and our rarest animals were not safe even in the most remote corners of the country. On one Perthshire estate alone, 9,849 weasels and stoats, 4,042 feral cats, 2,517 “hawks”, 2,517 crows, 1,239 foxes, 576 ravens, 56 pine martens, 37 eagles, 26 otters and eight polecats were culled in the decade leading up to 1900.”

During 1590 it was the churchwarden’s duty to keep control over the so-called vermin and he’d pay two shillings for an otter while later, 2/6d was the going bounty for sparrow heads and for weasels and stoats. In 1769 one could get “three polecats for one shilling”. Shakespeare mentioned the polecat in his play, “The Merry Wives of Windsor” where Mistress Quickly states “Polecats! There are fairer things than polecats, sure.”

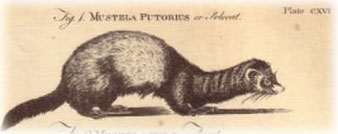

Encyclopaedia Britannica

There was a paragraph about Polecats in the 1771 edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica …

The putorius, or pole-cat, has unconnected toes, is of a dirty yellow colour, with a white mouth and ears. This animal is very destructive to birds and poultry. He conceals himself during the day; but steals into barns, dove-cotes, hen houses, etc. in the night, in order to catch his prey. He is a native of most parts of Europe.

I’m surprised to read that it was described as being a “dirty yellow colour”. Maybe it was a typo and should have been in the paragraph for the ferret!?

Persecution of the Polecat The polecat was also trapped for its fur, known as ‘fitch’, which was widely used in the early 19th century. In Dumfries, Scotland, there are records which show that 400 polecat pelts were sold at the old Fur Fair in 1829, and a total of 600 in 1831. However, in 1866, only 6 furs were available for sale there and after that year they stopped recording the number of pelts.

Polecat hunting was also a sport among the country squires of North Wales, Cheshire, Cumberland and Westmorland, where special packs of hounds were kept to hunt them down. However these days in the UK polecats are protected under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981. Certain methods of killing or taking Polecats are prohibited under the act, and it is an offence to set a trap for a polecat without obtaining a licence to do so.

BBC Clips of Polecat Kits

There are some short clips from the BBC Motion Gallery of polecats so if you’d like to see them, go to … ARKive website.

How to say Polecat in different languages

- Albanian: qelbësi

- Arabic: فأر الخيل

- Aragonese: fura

- Basque: ipurtats

- Belarusian: тхор лясны/ чорны (thor ljasny / čorny)

- Bosnian: tvor

- Breton: pudask

- Bulgarian: прът (pr’t )

- Catalan: turó

- Croatian: tvor

- Czech: tchoř tmavý

- Danish: ilder

- Dutch: bunzing

- Esperanto: putoro

- Estonian: tõhk / valgetuhkur

- Farsi [spoken in Iran]: موش خرماى وحشى اروپايى )ج.ش.(, خز, ظربان

- Finnish: hilleri

- French: putois

- Frisian[spoken in Friesland]: murd

- Friulian [spoken in NE Italy]: puçul, pufe, pudîs, spuç

- Galician: tourón

- German: waldiltis

- Greek: οζοϊκτίς, βρωμοκούναβο (ozoϊktis, vromokounavo )

- Hebrew: חמוס מצוי

- Hungarian: közönséges görény

- Indonesian: kuskus

- Irish (Gaeilge): firéad

- Italian: puzzola

- Japanese: ヨーロッパケナガイタチ

- Korean: 긴털족제비

- Latvian: sesks

- Lithuanian: juodasis šeškas

- Macedonian: обичен твор (običen tvor)

- Manx: assag vuinnaght

- Norwegian: ilder

- Occitan: catpudre

- Polish: tchórz zwyczajny

- Portuguese: toirão

- Romanian: dihor

- Romansh: telpi

- Romany [Gypsy]: mutsa-kandini

- Russian: хорёк лесной / черный (horjok lеsnoj / čеrnyj )

- Sami [spoken in Lapland]: čáhppesbuoidda

- Sardinian: půtzola

- Scottish (Gaelic): feòcallan

- Serbian: твор (-мрки) (tvor (-mrki))

- Slovak: tchor obyčajný, tchor tmavý

- Slovenian: dihur

- Sorbian (upper) [spoken in Saxony]: tchór

- Sorbian (lower) [spoken in Brandenburg]: twoŕ

- Spanish: turón europeo / mapurito

- Swazi: lí-cacá

- Swedish: iller

- Tagalog [Spoken in the Philippines]: polkat

- Thai: สัตว์จำพวกพังพอน

- Turkish: kokarca

- Ukrainian: тхiр лiсовий / чорний (thir lisovij / čornij )

- Vietnamese: loại chồn nhỏ

- Welsh (Cymraeag): ffwlbart

Interesting Links

For those wanting to learn more about the European Polecat, there are several sites which have a lot of information about them.

Mustela Putorius (ICUN Red List of Threatened Species)

Mustela Putorius (ICUN Red List of Threatened Species)

The Polecat (The Vincent Wildlife Trust)

The Polecat (The Vincent Wildlife Trust)

European Polecat Project by Thierry Lodé

European Polecat Project by Thierry Lodé

European Polecat (Comparative Mammalian Brain Collections)

European Polecat (Comparative Mammalian Brain Collections)

The Stinkards — Buffon’s Natural History – Volume IX by Georges Louis Leclerc de Buffon (Project Gutenberg)

The Stinkards — Buffon’s Natural History – Volume IX by Georges Louis Leclerc de Buffon (Project Gutenberg)

A pdf called The Animals in Chester’s Noah’s Flood by Lisa J Kiser

A pdf called The Animals in Chester’s Noah’s Flood by Lisa J Kiser

Return from European Polecat (Mustela putorius) to All About Ferrets

Proof that mustelids (ferrets), learn 5x faster than dogs…

https://youtu.be/Jk5_p3WWA4E

Incredible!! 😮